Their motive? They hated him for who his family was. And after all he'd done Eppolito believed the good guys actually had less honor than the crooks whose life he'd renounced.

14 years after the release of Mafia Cop, the title took on a new meaning when Eppolito and his one-time police partner Stephen Caracappa were convicted on a slew of charges for providing information to, and participating in murders for, mobster Anthony Casso. To say it put the book in a different light would be an understatement.

Until recently I've held Mafia Cop in the same headspace I have for Manos: The Hands of Fate; I know it's trash. I know everyone else interested in the subject knows it's trash. But I've had no wish to view it without the filter of someone else's commentary - in this case William Oldham and Guy Lawson's The Brotherhoods. Recently, however, a potential project came to mind and I decided to look though it in hopes of getting a little more background info.

As is often the case with books like this most of the heavy lifting was done by a coauthor. Mafia Cop is largely the work of journalist and prolific author Bob Drury. In a 2009 Popmatters interview Drury spoke of the book only in passing, giving more attention to his editing work for "Joe Dogs" Iannuzzi's autobiography before moving on from his true crime works.

Certainly Drury was more enthusiastic in the book's prologue, recalling meeting the subject at his home and in what we are told is a mob-favored restaurant. During the former meeting he's even lucky enough to be around when Eppolito receives a conveniently-timed thank-you note from the mother of someone whose life he'd saved after a plane crash "by reaching into the hole in his gut and pinching a severed artery" - though the book doesn't tell us when this happened so we can check this fantastic tale for ourselves. "He'd survived eight shootouts, killed at least one man, and his heroism was legend among New York's Finest."

The mood is a touch bleaker in the first three chapters. Drury chose to give us an in media res opening with Eppolito learning of the murders of a mobbed-up uncle and the uncle's criminal son, Jimmy and Jim-Jim. Louis Eppolito is horrified when he hears the news on the job, but his heightened emotions are quickly turned to fury when he calls the responding homicide division and, he tells us, overhears someone in the background blowing him off. Our title character responds with threats of violence against his fellow officers before the phone is taken from him and the cops handling the murder are summoned to explain the situation in person.

It turns out two mobsters were arrested at the scene and Homicide tried to keep Eppolito out of the loop because "We didn't want anybody to do anything stupid." Eppolito's continued furious protests only seem to prove their point, but Drury insists they are in fact judging him for what his family did. The contradiction in the narrative is made even worse by an entire chapter in this introduction showing Louis Eppolito's closeness to his criminal uncle Jimmy. Who wouldn't want to keep this investigation under impartial eyes?

At the onset, three trends in this story become immediately obvious. First is, of course, the glorification of violence by Eppolito. The second is the constant victimization of Eppolito. When Homicide is brought in to give their preliminary report of the double Jimmy murders we're told "The scene that followed had more of the feel of an interrogation than a briefing" without any explanation of what - if anything - was said to make Eppolito feel uncomfortable. Later that day we're also told Eppolito had the opportunity to chew out a fellow officer who thought he was making mocking comments out of earshot of the grieving title character.

The third trend is illustrated by a brag in the prologue. At the time Mafia Cop was written Eppolito had retired from the force and was trying to pivot into acting. Most famously he'd had a cameo in 1990's Goodfellas and was telling Drury that a wiseguy by the name of "Allie Boy" had made an offer to help him secure another role with a personal visit to the producers. While not explicitly confirmed the only Allie Boy mentioned in the book is the most famous holder of the nickname; Alphonse Persico, the son and would-be successor of Colombo boss Carmine Persico. And Allie Boy Persico was in jail at the time.

What I'm saying is nothing in this book can be taken at face value.

The main theme of the work is also made very clear from the start: "As he sat back and talked with equal ease about his personal experiences with both capo and cop, it became obvious that here was a cop who defied classification." Louis Eppolito is a very, very special person, and as such he deserves special treatment. His brutality is to be forgiven as the price paid for his exceptional service (the eleventh most decorated cop in NYPD history.) His fraternization with mobsters is perfectly fine because they are his real family and, in their own way, more honorable than the cops. "There were children who had lived to be teenagers, and pensioners who still had their life savings and, yes, even cops on The Job [sic] who thanked the Good Lord for Detective Eppolito's lack of discretion."

I realize Bob Drury probably wasn't getting paid to ask if it was too good to be true, but surely the thought must have crossed his mind at some point.

Louis Eppolito was the son of one Ralph "Fats the Gangster" Eppolito, and his childhood was not an easy one. He was born in a squalid neighborhood, was seriously ill with rheumatic fever in his first years, and was subject to regular physical abuse from his often-absent chronically ill father. One incident described that left me taken aback showed Ralph storming in on his son taking a shower and bludgeoning him with a 2x4 for the offense of responding to a call from his sister with "What?" Apparently not addressing her by her name despite being clearly preoccupied was disrespectful, and Ralph preached the importance of showing respect.

At no point does Drury consider what such a violent, loveless upbringing would do to the book's subject. Nor does he call into question the mindset of the abuser. Chapter nine is told entirely by Louis' mother Tess, and she paints her husband as a relatively minor hood overshadowed in the mob by his brothers Freddy and Jimmy. He was also out of work for a year as he recovered from a heart attack - a situation that forced his wife to fill in as the family's breadwinner. This would have been profoundly embarrassing in the macho culture of Cosa Nostra. I'd feel sorry for Ralph if he wasn't clearly coping by taking his anger out on his son.

Chapter nine also is disappointingly unsubstantial. Tess Eppolito is a typical Mafia wife in the sense that she's insulated from her husband's life of crime, and she has little to say about her son's childhood.

Ralph's concept of honor has him teaching his son to fight back mercilessly against those who wrong him, and as he matures Lou Eppolito is introduced to his father's coworkers and rackets. Ralph is quoted acknowledging to his son he is a criminal, but he still considers himself above a blue-collar worker because he's "got f**king honor and respect." These qualities are defined in the next paragraph thus: "They'd [the mob] fight for what they believed was right. And they were loyal." And yet, while Louis is immersed in the life of the Mafia, we're told Ralph wanted his son to go legit.

Ralph Eppolito's body gave up the ghost as Lou Eppolito entered adulthood and married his first wife - a brief marriage with little detail provided. Lou paints himself as directionless and simply in need of cash when, on a whim, he took the written exam for the NYPD and passed. Drury lays on a page and a half of praise for Eppolito's violent problem-solving solutions and contempt for desk workers and bureaucracy even before Eppolito puts in his application, but the first specific example he provides us isn't even on the job. In a story I'd first seen repeated in The Brotherhoods Eppolito solves a domestic violence complaint by putting on a disguise and ambushing the offender with a lead pipe. He tops this later with a claim that, after a fellow cop was nearly killed in Prospect Park, he and an off-duty posse donned pantyhose balaclavas and brutalized the junkies they suspected were responsible.

Apparently Drury thought no one in the early 90's questioned what use these cops were if they couldn't actually build a case within the confines of the law. Incidentally, only Eppolito's wanton violence gets a pass in Mafia Cop. An officer who allegedly threw a mugger into the polar bear cage at Prospect Park Zoo is denounced by the title character as a "badge abuser" and by Drury as a "nuclear bomb."

There's no shortage of incidents that must've given Drury pause as he transcribed them. Early on Eppolito stops a man he sees running for no apparent reason, "the guy spins around and drops a pistol [...] not one split second later a bank alarm went off on the opposite corner. [...] I was all over the television news that night explaining my 'sixth sense' to the tabloid and TV reporters. The newsmen in New York like to think of themselves as a cynical bunch, but, in truth, they eat that stuff up."

One smart thing Eppolito did, which Mafia Cop acknowledges, was build a rapport with reporters who would repeat his accounts in their articles. And yet Drury couldn't produce a single quote or headline about this unbelievable tale.

By Eppolito's account he was just about the only competent officer in his first assignment, the 63rd Precinct. When his fellow officers aren't slacking off they're committing the only act of corruption Mafia Cop treats as a crime: taking bribes. Eppolito eventually gets transferred to Harlem where, he says, he got his first Medal of Honor nomination by fighting his way out of a Black Liberation Army ambush. I would've used my newspapers.com free trial if they had an article going into detail on this, but I saw nothing promising in a search.

This seems like as good a time as any to point out that Eppolito wanted you to know, in no uncertain terms, that he was most definitely not a racist. We're told Ralph Eppolito was amicable in his dealings with black people as a numbers operator and taught his son not to hold any prejudices in language so uncharacteristically eloquent even Lou had to acknowledge it. Ralph even sought out a black washed-up boxer, Johnny Saxton, to train his son with the ulterior motive of ingraining tolerance. As a cop Louis Eppolito commented on his grim new assignment that he overcame the bigotry he was beginning to pick up with the realization "when I got to know my way around up there, I did find so many people who were human."

Emphasis in original.

Eppolito throws in multiple stories of heroism where he makes sure the readers knows the beneficiaries were black, and he decisively overshoots into full-blown white savior territory in chapter 17 immediately after the Prospect Park beatdown. He catches a black boy ("couldn't have been more than thirteen") who'd just robbed someone's purse but the sight of the malnourished child perp evokes pity in Lou, and his explanation that he was trying to feed his impoverished family reminds him of how his father lived. Eppolito makes a hasty cover-up and then, upon confirming the sorry state of the boy's family, calls up a number of cops who owed him a favor to chip in to buy the family groceries and finds the boy's mother a job in the process. The saccharine-sweet cherry on top is Eppolito waking one of the boy's little sisters: "Suddenly, still half-asleep, she threw her tiny arms around Louie's bull neck and whispered, "I love you." "

Back in the real world The Brotherhoods noted that, when Eppolito went on trial in 2006, he benefited from the judge barring character evidence because he couldn't stop using ethnic slurs when talking to someone who was wearing a wire.

While all this is going on Louis Eppolito plays fast and loose with regulations against associating with mobsters. While working the 63rd he admits to regularly spending time with Colombo capo "Jim Brown" Clemenza, and when he does try to keep to the rules he says it places an unfair burden on his social life. When planning for his second wedding Eppolito accepts a steep discount on the reception based on his family name and, as he becomes closer to his Uncle Jimmy, keeps a $3,000 cash gift under the rationale trying to return it would be "the highest form of disrespect."

The beginning of the end comes when Lou and his second wife Fran go to an Italian restaurant and, after finding out their bill was paid by Genovese capo Todo Marino, Lou gives him an old-fashioned kiss of respect. In a remarkable twist the exact moment of the kiss, in a restaurant, is caught in an FBI surveillance photo, and after the Feds give our hero grief they turn it over to NYPD Internal Affairs. Eppolito's contempt for Federal law enforcement is a cross-pollination of his father's (complete with a variant of the "Forever Bothering Italians" backronym) and a beat cop's disdain for overhyped hicks with no street smarts. When Uncle Jimmy gets whacked, the official turning point in the story, one Fed even has to nerve to say to Lou's face "The apple doesn't fall too far from the tree."

And then. because Lou apparently really is liable to do something stupid regarding his uncle, he gets a face-to-face meeting with Gambino boss Paul Castellano in his Staten Island mansion where Big Paul persuades him to just let it go.

This isn't the first time Eppolito says he met a boss as an adult; allegedly Castellano's predecessor Carlo Gambino made an appearance at Ralph Eppolito's wake. This is at least within the realm of possibility - Castellano famously lost face for skipping his underboss Neil Dellacroce's wake - but the book noting Gambino didn't make his appearance until FBI surveillance left makes me skeptical. The Castellano meeting, however, is a joke.

This was another scene The Brotherhoods mentioned - "a fantasy bordering on a delusion" Major Case Detective William Oldham called it - but he and his journalist coauthor Guy Lawson left out the best part. Eppolito says Castellano tried to bribe him and he had the pleasure of rebuking the reputed boss of bosses.

From here on in Eppoltio becomes a true "Mafia Cop" - acting Italian at home and getting cozier with Mafiosi. Lou's next self-reported crime sees him respond to a threat from prospective Colombo member Frankie Carbone by menacing him with a sawn-off shotgun until he craps his pants. This time it somehow feels different: "I was walking like a wiseguy, talking like a wiseguy."

Again The Brotherhoods' recap leaves out the best part. After this, to keep Frankie from taking revenge, he and Eppolito go to a full-blown official Mafia sitdown overseen by the Lucchese's Christy Tick Furnari to bury the hatchet.

The problem with this story, besides it being f**king bulls**t, is that it's now impossible to take Eppolito seriously as an honest cop. How can we trust anyone supposedly in this deep with the mob?

If you'll indulge me going off on a tangent, this brings to mind another bad Mafia book: 2017's Last Don Standing. Written by journalist Larry McShane and TV producer Dan Pearson, it's effectively the self-serving autobiography of Ralph Natale, an ineffectual boss of the Philly mob whose place in history is for being the first official Mafia boss to cooperate. Last Don Standing's most famous claim is that Natale was secretly 'made' (officially inducted into the Mafia) in the 1970s by both then-Philadelphia-boss Angelo Bruno and Carlo Gambino. This claim contradicts Natale's earlier reports, and no one takes it seriously.

In reality Natale was made by his future nominal underboss Joey Merlino while the latter was wrapping up a war for control of the family with boss John Stanfa. An induction by a pretender is questionable enough, but Natale complicates things further by insisting the Sicilian-born Stanfa wasn't eligible for the top job either under what he claims are US Mafia rules. As my fellow Redditor and partial inspiration Nizar Soccer explained, "This line of thought throws a huge wrench into current-day Philadelphia, considering Joey Merlino was originally made under Stanfa, and thus anyone initiated under Merlino (including Ralph Natale) is not technically legitimate."

Conveniently, however, Natale's secret induction by two sitting bosses sidesteps this whole mess.

What I'm getting at is at least Ralph Natale's lies give us a coherent narrative. Eppolito and Drury are just digging a deeper hole.

Mafia Cop's climax comes when a copy of an NYPD Intelligence file on heroin trafficker Rosario Gambino is found in Gambino's home after his arrest, and Louis Eppolito stands accused of providing him with it. Eppolito's retelling of the story begins with him saying his only dealing with Rosario was choking him for making an obscene gesture at him. In a visit to the Intelligence Division for an unrelated case, however, one officer presents him with Rosario's file - practically thrusting it into Eppolito's hands. Some time later after Eppolito returned it he's called before Internal Affairs and asked to explain why the copy of the file found in Rosario's house has his fingerprints on it.

Drury includes interviews with one Steve Gardell, a police union rep whose support of Eppolito is absolute. At one point Gardell says he went to one Frank Schilling, described as Brooklyn's Chief of Detectives, to plead Eppolito's case only to be told "It's in his genes. You can't separate the mob background, the mob Family, from the cop. It's in his blood." Right or wrong, IA and the brass just want to be done with Eppolito.

In 2000 Gardell was charged with, among other things, taking a kickback to funnel his union's pension funds into a mob stock scam. He cut a plea deal, and Rick Porrello's AmericanMafia.com would dub him the "Other Mafia Cop."

And can I just say this was a pain in the ass to verify? News coverage of the indictment comes up easy on a Google search, but there's nothing on the resolution. I had to use Congressional hearings records and run Gardell's name through the BOP's inmate locator. All rather suspicious if you ask me.

At the time this book was written this was the worst experience of Eppolito's life. He was suspended, shamed in the press, and only got by on the charity of sympathetic fellow officers. The sight of the former tough guy being reduced to tears is presented as a shock to his family, but Eppolito undermines the reader's sympathy by admitting to fantasizing about brutally murdering the accusing IA panel in front of their children. By the time he finally pulls it together he also comes to the revelation that, because mobsters offered him jobs in his time of need, they were indeed the more honorable society.

Louis Eppolito, of course, skated on his first charges of providing intel to the mob. The reason? Accoridng to Eppolito and Gardell, the only complete fingerprints on the documents found in Rosario Gambino's home were photocopies, which were left on the original when Eppolito briefly handled it and then somehow were also transferred onto the copy when it was duplicated.

If anyone can explain to me how such a thing is even possible, I would greatly appreciate it.

Critically, I repeat, this is the reason as stated by Eppolito and Gardell. Hugh Mo, the commissioner who would've presided over Eppolito's departmental trial, is quoted only in generalities on his feeling the evidence isn't strong enough to proceed regarding his decision to scuttle the trial. The only thing outside observers seem to agree on is the dismissal looked very fishy.

After his acquittal Eppolito gets one more chance to yell at the NYPD's Chief of Detectives Richard NiCastro and get denied his choice of reassignment. The last four years of Eppolito's career before his 1989 retirement were apparently so uneventful they required nothing more than a two page epilogue and the pithy final sentence "The New York City Police Department had finally managed to rid itself of one of its worthiest cops." I didn't even get the info I was looking for regarding his film debut.

So, can we believe a word of this?

Eppolito's lies regarding his law enforcement career go back to before his first day on the job. By his own account, when asked in the application process for his personal history, he disclosed all of his Mafia ties, and his brutal honesty won him the shocked admiration of his recruiter. In his 2006 book Mob Cops, journalist Greg B. Smith noted no such disclosures appear in his records.

Brotherhoods author William Oldham was one of the NY cops who kept the investigation of Eppolito and Stephen Caracappa going when the FBI first let the case go cold. He bought a copy of Mafia Cop upon release and considered it a bad joke. He drew attention to both the off-duty piping and a later enhanced interrogation incident where our hero dunks a perp's head into a solution of scalding water and ammonia until "[his] face was mutating into a giant purple blotch." This, Oldham states, would have gotten Eppolito himself in hot water with the staff of New York's jails. When assembling the evidence Oldham looked through Mafia Cop again to compare Eppolito's stories to the official records. His conclusion: "Nothing checked out. [...] Everything about his police life had to be taken to be a fantasy."

Now, The Brotherhoods isn't perfect. Oldham attributes to the book an Eppolito tall tale of stopping a hijacking that wasn't there. But Eppolito's claims were also cross-checked by another NY cop turned author, Tommy Dades. In his 2009 history of the case, Friends of the Family (coauthors ADA Mike Vecchione and writer David Fisher,) Dades noted there were no records of Eppolito participating in any shootouts despite his boasting of taking the lives of criminals in the line of duty.

Oldham also brings attention to complains of misconduct that Mafia Cop left out. As a cop himself, Oldham indicates he might've given Eppolito (and Caracappa) the benefit of the doubt; filings complaints is, for a perp, "[the] easiest way to f**k with a cop", but the number of complaints was disproportionately high against Eppolito's actual low number of arrests. Tommy Dades would've had more to say on the matter, but by the time he was on the case and Vecchione spoke to IA on his behalf, Eppolito and Caracappa's files had mysteriously vanished.

Probably the most damning condemnation of Mafia Cop came from Louis Eppolito himself. During the appeals for his 2006 conviction he complained about his lawyer Bruce Cutler not letting him take the stand as his own defense witness. At this point he was put under interrogation by prosecutor Robert Henoch, and admitted he exaggerated at times to maintain his tough-guy persona.

Is there anything in the book that's more interesting in hindsight? Less than you'd expect.

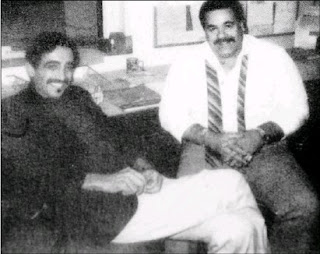

There's a now-notorious picture of Eppolito and Caracappa from their time in the force titled "The two Godfathers of the NYPD" in Mafia Cop, but in the text itself appearances by Lou's co-conspirator are surprisingly few and far between.

The only thing that caught my eye was a throwaway reference in the prologue. In a list of Eppolito's accomplishments we get "He spoke of [...] the crack hooker whose murderer he'd spent his off-duty hours tracking down, "because whores got mothers, too." " The details are never provided but I immediately thought of the murder of one Virginia Robertson - as did Greg Smith, who described the case in detail in Mob Cops. In summary, Robertson's murder remains unsolved because Eppolito's approach to closing the case involved coercing the only witness to frame an innocent man. (Before you ask the patsy, Barry Gibbs, wasn't black, but the victim and witness were.)

I'll close by answering the question I know anyone unfamiliar with the case has. Yes, there is a direct line to be drawn between the publication of Mafia Cop and Eppolito's undoing. Two, actually - both from the inclusion of the "Godfathers" photo.

Anthony Casso, Eppolito and Caracappa's main patron, worked with them through a middleman - a mob associate named Burton Kaplan who would be the star witness in the 2006 trial. Casso himself only saw his cops in person once, and Kaplan did his best to keep him from learning their names. But when Mafia Cop came out Casso read it, recognized Eppolito and Caracappa, and would be the first to blow the whistle during his unsuccessful attempt to cooperate.

And then there was Eppolito's promotional appearance on the Sally Jesse Raphael Show in 1992 (headphones not recommended.) One Betty Hydell would watch a rerun of this episode and recognize Eppolito as a cop who'd been looking for her criminal son Jimmy Hydell the day he was kidnapped for Anthony Casso - an ID confirmed by Mafia Cop. She informed both the FBI and Tommy Dades, and would also be a prosecution witness to corroborate Kaplan's claim of paying the cops to kidnap Jimmy Hydell.

For all his talk about the values of the Mafia, Eppolito never learned the golden rule of organized crime as codified in any George Anastasia book: Make money, not headlines.

No comments:

Post a Comment